www.taiwan-database.net

The ROC Constitution

(Also on this page: Sun Yat-sen's "Three Principles of the People")

- The Constitution of the Republic of China (full text)

- Chapter I. General Provisions

- Chapter II. Rights and Duties of the People

- Chapter III. The National Assembly

- Chapter IV. The President

- Chapter V. Administration

- Chapter VI. Legislation

- Chapter VII. Judiciary

- Chapter VIII. Examination

- Chapter IX. Control

- Chapter X. Powers of the Central and Local Governments

- Chapter XI. System of Local Government

- Chapter XII. Election, Recall, Initiative and Referendum

- Chapter XIII. Fundamental National Policies

- Chapter XIV. Enforcement and Amendment of the Constitution

- (~ in Chinese) 中華民國憲法【全文】

- 第一章 總綱

- 第二章 人民之權利與義務

- 第三章 國民大會

- 第四章 總統

- 第五章 行政

- 第六章 立法

- 第七章 司法

- 第八章 考試

- 第九章 監察

- 第十章 中央與地方之權限

- 第十一章 地方制度

- 第十二章 選舉 罷免 創制決

- 第十三章 基本國策

- 第十四章 憲法之施行及修改

- Temporary Provisions Effective During the Period of Communist Rebellion

- Original version (1948)

- Amended version (1960)

- Amended version (1966)

- Amended, final version (1972)

- (~ in Chinese) 動員戡亂時期臨時條款【全文】

- 動員戡亂時期臨時條款(民國 37 年 / 1948)

- 動員戡亂時期臨時條款 修正(民國 49 年 / 1960)

- 動員戡亂時期臨時條款 修正(民國 55 年 / 1966)

- 動員戡亂時期臨時條款 修正(民國 61 年 / 1972)

- The Additional Articles (full texts)

- First Revision (1991)

- Second Revision (1992)

- Third Revision (1994)

- Fourth Revision (1997)

- Fifth Revision (1999)

- Sixth Revision (2000)

- Seventh Revision (2004/2005)

- (~ in Chinese) 中華民國憲法增修條文【全文】

- 中華民國憲法第一次增修條文 (1991)

- 中華民國憲法第二次增修條文 (1992)

- 中華民國憲法第三次增修條文 (1994)

- 中華民國憲法第四次增修條文 (1997)

- 中華民國憲法第五次增修條文 (1999)

- 中華民國憲法第六次增修條文 (2000)

- 中華民國憲法第七次增修條文 (2004/2005)

- Explanations to the ROC Constitution and its revisions

- Enactment and features

- Temporary Provisions

- First revision (1991)

- Second revision (1992)

- Third revision (1994)

- Fourth revision (1997)

- Fifth revision (1999)

- Sixth revision (2000)

- Seventh revision (2004/2005)

- The Three Principles of the People (full text)

- Author’s Preface

- The Principle of Nationalism

- Lecture One [Jan. 27, 1924]

- Lecture Two [Feb. 3, 1924]

- Lecture Three [Feb. 10, 1924]

- Lecture Four [Feb. 17, 1924]

- Lecture Five [Feb. 24, 1924]

- Lecture Six [March 2, 1924]

- The Principle of Democracy

- Lecture One [March 9, 1924]

- Lecture Two [March 16, 1924]

- Lecture Three [March 23, 1924]

- Lecture Four [April 13, 1924]

- Lecture Five [April 20, 1924]

- Lecture Six [April 26, 1924]

- The Principle of Livelihood

- Lecture One [Aug. 3, 1924]

- Lecture Two [Aug. 10, 1924]

- Lecture Three [Aug. 17, 1924]

- Lecture Four [Aug. 24, 1924]

- Dr. Sun Yat-sen’s Will

- 三民主義 【全文】

|

|

|

|

Notes

This page presents the full text of the ROC Constitution in English and Chinese with all amendments, likewise in English and Chinese, plus explanations (including a short timeline). A general, brief introduction to the ROC Constitution can be found here.

In addition, this page contains the full text of Sun Yat-sen’s Three Principles of the People (sanmin zhuyi 三民主義) which can be considered an important intellectual foundation of the ROC. The English translation of the original Chinese version was done by Frank W. Price (1895-1974).

For offline use, a PDF file that shows the contents of the ROC Constitution and relevant material on this page—73 pages in A4 format, file size: 2.1 MB—can be opened for free download by clicking here. Another PDF file with the Three Principles of the People (156 pages in A4 format, file size: 4.6 MB) is accessible here.===== ===== ===== ===== =====

◆ The Constitution of the Republic of China (full text)

- Chapter I. General Provisions

- Chapter II. Rights and Duties of the People

- Chapter III. The National Assembly

- Chapter IV. The President

- Chapter V. Administration

- Chapter VI. Legislation

- Chapter VII. Judiciary

- Chapter VIII. Examination

- Chapter IX. Control

- Chapter X. Powers of the Central and Local Governments

- Chapter XI. System of Local Government

- Chapter XII. Election, Recall, Initiative and Referendum

- Chapter XIII. Fundamental National Policies

- Chapter XIV. Enforcement and Amendment of the Constitution

(Jump to Explanations to the ROC Constitution and its revisions)

++++++++++ TOP HOME [next chapter] ++++++++++

(Adopted by the National Assembly on December 25, 1946, promulgated by the National Government on January 1, 1947, and effective from December 25, 1947.)

The National Assembly of the Republic of China, by virtue of the mandate received from the whole body of citizens, in accordance with the teachings bequeathed by Dr. Sun Yat-sen in founding the Republic of China, and in order to consolidate the authority of the State, safeguard the rights of the people, ensure social tranquility, and promote the welfare of the people, do hereby establish this Constitution, to be promulgated throughout the country for faithful and perpetual observance by all.

Chapters and sections of the ROC Constitution

| Chapter | Articles | Contents | (in Chinese) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chapter I | 1-6 | General Provisions | 第一章 總綱 |

| Chapter II | 7-24 | Rights and Duties of the People | 第二章 人民之權利與義務 |

| Chapter III | 25-34 | The National Assembly | 第三章 國民大會 |

| Chapter IV | 35-52 | The President | 第四章 總統 |

| Chapter V | 53-61 | Administration | 第五章 行政 |

| Chapter VI | 62-76 | Legislation | 第六章 立法 |

| Chapter VII | 77-82 | Judiciary | 第七章 司法 |

| Chapter VIII | 83-89 | Examination | 第八章 考試 |

| Chapter IX | 90-106 | Control | 第九章 監察 |

| Chapter X | 107-111 | Powers of the Central and Local Governments | 第十章 中央與地方之權限 |

| Chapter XI | 112-128 | System of Local Government | 第十一章 地方制度 |

| —Section 1 | 112-120 | The Province | 第一節:省 |

| —Section 2 | 121-128 | The Hsien | 第二節:縣 |

| Chapter XII | 129-136 | Election, Recall, Initiative, and Referendum | 第十二章 選舉 罷免 創制決 |

| Chapter XIII | 137-169 | Fundamental National Policies | 第十三章 基本國策 |

| —Section 1 | 137-140 | National Defense | 第一節:國防 |

| —Section 2 | 141 | Foreign Policy | 第二節:外交 |

| —Section 3 | 142-151 | National Economy | 第三節:國民經濟 |

| —Section 4 | 152-157 | Social Security | 第四節:社會安全 |

| —Section 5 | 158-167 | Education and Culture | 第五節:教育文化 |

| —Section 6 | 168-169 | Frontier Regions | 第六節:邊疆地區 |

| Chapter XIV | 170-175 | Enforcement and Amendment of the Constitution | 第十四章 憲法之施行及修改 |

TOP HOME [◆ Directory ROC Constitution (English)]

+++++ +++++ +++++ +++++ +++++ +++++ +++++ +++++ +++++ +++++

Chapter I. General Provisions

| Article 1 | The Republic of China, founded on the Three Principles of the People, shall be a democratic republic of the people, to be governed by the people and for the people. |

| Article 2 | The sovereignty of the Republic of China shall reside in the whole body of citizens. |

| Article 3 | Persons possessing the nationality of the Republic of China shall be citizens of the Republic of China. |

| Article 4 | The territory of the Republic of China according to its existing national boundaries shall not be altered except by resolution of the National Assembly. |

| Article 5 | There shall be equality among the various racial groups in the Republic of China. |

| Article 6 | The national flag of the Republic of China shall be of red ground with a blue sky and a white sun in the upper left corner. |

TOP HOME [◆ Directory ROC Constitution (English)]

Chapter II. Rights and Duties of the People

| Article 7 | All citizens of the Republic of China, irrespective of sex, religion, race, class, or party affiliation, shall be equal before the law. |

| Article 8 | Personal

freedom shall be guaranteed to the people. Except in case of flagrante delicto

as provided by law, no person shall be arrested or detained otherwise than by a

judicial or a police organ in accordance with the procedure prescribed by law.

No person shall be tried or punished otherwise than by a law court in

accordance with the procedure prescribed by law. Any arrest, detention, trial,

or punishment which is not in accordance with the procedure prescribed by law

may be resisted.

When a person is arrested or detained on suspicion of having committed a crime, the organ making the arrest or detention shall in writing inform the said person, and his designated relative or friend, of the grounds for his arrest or detention, and shall, within 24 hours, turn him over to a competent court for trial. The said person, or any other person, may petition the competent court that a writ be served within 24 hours on the organ making the arrest for the surrender of the said person for trial. The court shall not reject the petition mentioned in the preceding paragraph, nor shall it order the organ concerned to make an investigation and report first. The organ concerned shall not refuse to execute, or delay in executing, the writ of the court for the surrender of the said person for trial. When a person is unlawfully arrested or detained by any organ, he or any other person may petition the court for an investigation. The court shall not reject such a petition, and shall, within 24 hours, investigate the action of the organ concerned and deal with the matter in accordance with law. |

| Article 9 | Except those in active military service, no person shall be subject to trial by a military tribunal. |

| Article 10 | The people shall have freedom of residence and of change of residence. |

| Article 11 | The people shall have freedom of speech, teaching, writing and publication. |

| Article 12 | The people shall have freedom of privacy of correspondence. |

| Article 13 | The people shall have freedom of religious belief. |

| Article 14 | The people shall have freedom of assembly and association. |

| Article 15 | The right of existence, the right to work and the right of property shall be guaranteed to the people. |

| Article 16 | The people shall have the right of presenting petitions, lodging complaints, or instituting legal proceedings. |

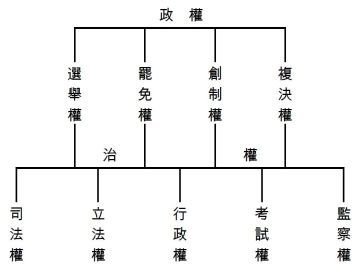

| Article 17 | The people shall have the right of election, recall, initiative and referendum. |

| Article 18 | The people shall have the right of taking public examinations and of holding public offices. |

| Article 19 | The people shall have the duty of paying taxes in accordance with law. |

| Article 20 | The people shall have the duty of performing military service in accordance with law. |

| Article 21 | The people shall have the right and the duty of receiving citizens' education. |

| Article 22 | All other freedoms and rights of the people that are not detrimental to social order or public welfare shall be guaranteed under the Constitution. |

| Article 23 | All the freedoms and rights enumerated in the preceding Articles shall not be restricted by law except such as may be necessary to prevent infringement upon the freedoms of other persons, to avert an imminent crisis, to maintain social order or to advance public welfare. |

| Article 24 | Any public functionary who, in violation of law, infringes upon the freedom or right of any person shall, in addition to being subject to disciplinary measures in accordance with law, be held responsible under criminal and civil laws. The injured person may, in accordance with law, claim compensation from the State for damage sustained. |

TOP HOME [◆ Directory ROC Constitution (English)]

Chapter III. The National Assembly

| Article 25 | The National Assembly shall, in accordance with the provisions of this Constitution, exercise political powers on behalf of the whole body of citizens. |

| Article 26 | The

National Assembly shall be composed of the following delegates:

One delegate shall be elected from each hsien, municipality, or area of equivalent status. In case its population exceeds 500,000, one additional delegate shall be elected for each additional 500,000. Areas equivalent to hsien or municipalities shall be prescribed by law; Delegates to represent Mongolia shall be elected on the basis of four for each league and one for each Special banner; The number of delegates to be elected from Tibet shall be prescribed by law; The number of delegates to be elected by various racial groups in frontier regions shall be prescribed by law; The number of delegates to be elected by Chinese citizens residing abroad shall be prescribed by law; The number of delegates to be elected by occupational groups shall be prescribed by law; The number of delegates to be elected by women's organizations shall be prescribed by law. |

| Article 27 | The

function of the National Assembly shall be as follows:

To elect the President and the Vice President; To recall the President and the Vice President; To amend the Constitution; and To vote on proposed Constitutional amendments submitted by the Legislative Yuan by way of referendum. With respect to the rights of initiative and referendum, except as is provided in Items 3 and 4 of the preceding paragraph, the National Assembly shall make regulations pertaining thereto and put them into effect after the above-mentioned two political rights shall have been exercised in one half of the hsien and municipalities of the whole country. |

| Article 28 | Delegates

to the National Assembly shall be elected every six years.

The term of office of the delegates to each National Assembly shall terminate on the day on which the next National Assembly convenes. No incumbent government official shall, in the electoral area where he holds office, be elected delegate to the National Assembly. |

| Article 29 | The National Assembly shall be convoked by the President to meet 90 days prior to the date of expiration of each presidential term. |

| Article 30 | An

extraordinary session of the National Assembly shall be convoked in any one of

the following circumstances:

When, in accordance with the provisions of Article 49 of this Constitution, a new President and a new Vice President are to be elected; When, by resolution of the Control Yuan, an impeachment of the President or the Vice President is instituted; When, by resolution of the Legislative Yuan, an amendment to the Constitution is proposed; and When a meeting is requested by not less than two-fifths of the delegates to the National Assembly. When an extraordinary session is to be convoked in accordance with Item 1 or Item 2 of the preceding paragraph, the President of the Legislative Yuan shall issue the notice of convocation; when it is to be convoked in accordance with Item 3 or Item 4, it shall be convoked by the President of the Republic. |

| Article 31 | The National Assembly shall meet at the seat of the Central Government. |

| Article 32 | No delegate to the National Assembly shall be held responsible outside the Assembly for opinions expressed or votes cast at meetings of the Assembly. |

| Article 33 | While the Assembly is in session, no delegate to the National Assembly shall, except in case of flagrante delicto, be arrested or detained without the permission of the National Assembly. |

| Article 34 | The organization of the National Assembly, the election and recall of delegates to the National Assembly, and the procedure whereby the National Assembly is to carry out its functions, shall be prescribed by law. |

TOP HOME [◆ Directory ROC Constitution (English)]

Chapter IV. The President

| Article 35 | The President shall be the head of the State and shall represent the Republic of China in foreign relations. |

| Article 36 | The President shall have supreme command of the land, sea and air forces of the whole country. |

| Article 37 | The President shall, in accordance with law, promulgate laws and issue mandates with the counter-signature of the President of the Executive Yuan or with the counter-signatures of both the President of Executive Yuan and the Ministers or Chairmen of Commissions concerned. |

| Article 38 | The President shall, in accordance with the provisions of this Constitution, exercise the powers of concluding treaties, declaring war and making peace. |

| Article 39 | The President may, in accordance with law, declare martial law with the approval of, or subject to confirmation by, the Legislative Yuan. When the Legislative Yuan deems it necessary, it may by resolution request the President to terminate martial law. |

| Article 40 | The President shall, in accordance with law, exercise the power of granting amnesties, pardons, remission of sentences and restitution of civil rights. |

| Article 41 | The President shall, in accordance with law, appoint and remove civil and military officials. |

| Article 42 | The President may, in accordance with law, confer honors and decorations. |

| Article 43 | In case of a natural calamity, an epidemic, or a national financial or economic crisis that calls for emergency measures, the President, during the recess of the Legislative Yuan, may, by resolution of the Executive Yuan Council, and in accordance with the Law on Emergency Orders, issue emergency orders, proclaiming such measures as may be necessary to cope with the situation. Such orders shall, within one month after issuance, be presented to the Legislative Yuan for confirmation; in case the Legislative Yuan withholds confirmation, the said orders shall forthwith cease to be valid. |

| Article 44 | In case of disputes between two or more Yuan other than those concerning which there are relevant provisions in this Constitution, the President may call a meeting of the Presidents of the Yuan concerned for consultation with a view to reaching a solution. |

| Article 45 | Any citizen of the Republic of China who has attained the age of 40 years may be elected President or Vice President. |

| Article 46 | The election of the President and the Vice President shall be prescribed by law. |

| Article 47 | The President and the Vice President shall serve a term of six years. They may be re-elected for a second term. |

| Article 48 | The

President shall, at the time of assuming office, take the following oath:

"I do solemnly and sincerely swear before the people of the whole country that I will observe the Constitution, faithfully perform my duties, promote the welfare of the people, safeguard the security of the State, and will in no way betray the people's trust. Should I break my oath, I shall be willing to submit myself to severe punishment by the State. This is my solemn oath." |

| Article 49 | In case the office of the President should become vacant, the Vice President shall succeed until the expiration of the original presidential term. In case the office of both the President and the Vice President should become vacant, the President of the Executive Yuan shall act for the President; and, in accordance with the provisions of Article 30 of this Constitution, an extraordinary session of the National Assembly shall be convoked for the election of a new President and a new Vice President, who shall hold office until the completion of the term left unfinished by the preceding President. In case the President should be unable to attend to office due to any cause, the Vice President shall act for the President. In case both the President and the Vice President should be unable to attend to office, the President of the Executive Yuan shall act for the President. |

| Article 50 | The President shall be relieved of his functions on the day on which his term of office expires. If by that time, the succeeding President has not yet been elected, or if the President-elect and the Vice-President-elect have not yet assumed office, the President of the Executive Yuan shall act for the President. |

| Article 51 | The period during which the President of the Executive Yuan may act for the President shall not exceed three months. |

| Article 52 | The President shall not, without having been recalled, or having been relieved of his functions, be liable to criminal prosecution unless he is charged with having committed an act of rebellion or treason. |

TOP HOME [◆ Directory ROC Constitution (English)]

Chapter V. Administration

| Article 53 | The Executive Yuan shall be the highest administrative organ of the state. |

| Article 54 | The Executive Yuan shall have a President, a Vice President, a certain number of Ministers and Chairmen of Commissions, and a certain number of Ministers without Portfolio. |

| Article 55 | The

President of the Executive Yuan shall be nominated and, with the consent of the

Legislative Yuan, appointed by the President of the Republic.

If, during the recess of the Legislative Yuan, the President of the Executive Yuan should resign or if his office should become vacant, his functions shall be exercised by the Vice President of the Yuan, acting on his behalf, but the President of the Republic shall, within 40 days, request a meeting of the Legislative Yuan to confirm his nominee for the vacancy. Pending such confirmation, the Vice President of the Executive Yuan shall temporarily exercise the functions of the President of the said Yuan. |

| Article 56 | The Vice President of the Executive Yuan, Ministers and Chairmen of Commissions, and Ministers without Portfolio shall be appointed by the President of the Republic upon the recommendation of the President of the Executive Yuan. |

| Article 57 | The

Executive Yuan shall be responsible to the Legislative Yuan in accordance with

the following provisions:

The Executive Yuan has the duty to present to the Legislative Yuan a statement of its administrative policies and a report on its administration. While the Legislative Yuan is in session, Members of the Legislative Yuan shall have the right to question the President and the Ministers and Chairmen of Commissions of the Executive Yuan; If the Legislative Yuan does not concur in any important policy of the Executive Yuan, it may, by resolution, request the Executive Yuan to alter such a policy. With respect to such resolution, the Executive Yuan may, with the approval of the President of the Republic, request the Legislative Yuan for reconsideration. If, after reconsideration, two-thirds of the Members of the Legislative Yuan present at the meeting uphold the original resolution, the President of the Executive Yuan shall either abide by the same or resign from office; If the Executive Yuan deems a resolution on a statutory, budgetary, or treaty bill passed by the Legislative Yuan difficult of execution, it may, with the approval of the President of the Republic and within ten days after its transmission to the Executive Yuan, request the Legislative Yuan to reconsider the said resolution. If after reconsideration, two-thirds of the Members of the Legislative Yuan present at the meeting uphold the original resolution, the President of the Executive Yuan shall either abide by the same or resign from office. |

| Article 58 | The

Executive Yuan shall have an Executive Yuan Council, to be composed of its

President, Vice President, various Ministers and Chairmen of Commissions, and

Ministers without Portfolio, with its President as Chairman.

Statutory or budgetary bills or bills concerning martial law, amnesty, declaration of war, conclusion of peace, treaties, and other important affairs, all of which are to be submitted to the Legislative Yuan, as well as matters that are of common concern to the various Ministries and Commissions, shall be presented by the President and various Ministers and Chairmen of Commissions of the Executive Yuan to the Executive Yuan Council for decision. |

| Article 59 | The Executive Yuan shall, three months before the beginning of each fiscal year, present to the Legislative Yuan the budgetary bill for the following fiscal year. |

| Article 60 | The Executive Yuan shall, within four months after the end of each fiscal year, present final accounts of revenues and expenditures to the Control Yuan. |

| Article 61 | The organization of the Executive Yuan shall be prescribed by law. |

TOP HOME [◆ Directory ROC Constitution (English)]

Chapter VI. Legislation

| Article 62 | The Legislative Yuan shall be the highest legislative organ of the State, to be constituted of members elected by the people. It shall exercise legislative power on behalf of the people. |

| Article 63 | The Legislative Yuan shall have the power to decide by resolution upon statutory or budgetary bills or bills concerning material law, amnesty, declaration of war, conclusion of peace or treaties, and other important affairs of the State. |

| Article 64 | Members

of the Legislative Yuan shall be elected in accordance with the following

provisions:

Those to be elected from the provinces and by the municipalities under the direct jurisdiction of the Executive Yuan shall be five for each province or municipality with a population of not more than 3,000,000, one additional member shall be elected for each additional 1,000,000 in a province or municipality whose population is over 3,000,000; Those to be elected from Mongolian Leagues and Banners; Those to be elected from Tibet; Those to be elected by various racial groups in frontier regions; Those to be elected by Chinese citizens residing abroad; and Those to be elected by occupational groups. The election of Members of the Legislative Yuan and the number of those to be elected in accordance with Items 2 to 6 of the preceding paragraph shall be prescribed by law. The number of women to be elected under the various items enumerated in the first paragraph shall be prescribed by law. |

| Article 65 | Members of the Legislative Yuan shall serve a term of three years, and shall be re-eligible. The election of Members of the Legislative Yuan shall be completed within three months prior to the expiration of each term. |

| Article 66 | The Legislative Yuan shall have a President and a Vice President, who shall be elected by and from among its Members. |

| Article 67 | The

Legislative Yuan may set up various committees.

Such committees may invite government officials and private persons concerned to be present at their meetings to answer questions. |

| Article 68 | The Legislative Yuan shall hold two sessions each year, and shall convene of its own accord. The first session shall last from February to the end of May, and the second session from September to the end of December. Whenever necessary a session may be prolonged. |

| Article 69 | In any of

the following circumstances, the Legislative Yuan may hold an extraordinary

session:

At the request of the President of the Republic; Upon the request of not less than one-fourth of its members. |

| Article 70 | The Legislative Yuan shall not make proposals for an increase in the expenditures in the budgetary bill presented by the Executive Yuan. |

| Article 71 | At the meetings of the Legislative Yuan, the Presidents of the various Yuan concerned and the various Ministers and Chairmen of Commissions concerned may be present to give their views. |

| Article 72 | Statutory bills passed by the Legislative Yuan shall be transmitted to the President of the Republic and to the Executive Yuan. The President shall, within ten days after receipt thereof, promulgate them; or he may deal with them in accordance with the provisions of Article 57 of this Constitution. |

| Article 73 | No Member of the Legislative Yuan shall be held responsible outside the Yuan for opinions expressed or votes cast in the Yuan. |

| Article 74 | No Member of the Legislative Yuan shall, except in case of flagrante delicto, be arrested or detained without the permission of the Legislative Yuan. |

| Article 75 | No Member of the Legislative Yuan shall concurrently hold a government post. |

| Article 76 | The organization of the Legislative Yuan shall be prescribed by law. |

TOP HOME [◆ Directory ROC Constitution (English)]

Chapter VII. Judiciary

| Article 77 | The Judicial Yuan shall be the highest judicial organ of the State and shall have charge of civil, criminal, and administrative cases, and over cases concerning disciplinary measures against public functionaries. |

| Article 78 | The Judicial Yuan shall interpret the Constitution and shall have the power to unify the interpretation of laws and orders. |

| Article 79 | The

Judicial Yuan shall have a President and a Vice President, who shall be

nominated and, with the consent of the Control Yuan, appointed by the President

of the Republic.

The Judicial Yuan shall have a number of Grand Justices to take charge of matters specified in Article 78 of this Constitution, who shall be nominated and, with the consent of the Control Yuan, appointed by the President of the Republic. Article 80 Judges shall be above partisanship and shall, in accordance with law, hold trials independently, free from any interference. |

| Article 81 | Judges shall hold office for life. No judge shall be removed from office unless he has been guilty of a criminal offense or subjected to disciplinary measure, or declared to be under interdiction. No judge shall, except in accordance with law, be suspended or transferred or have his salary reduced. |

| Article 82 | The organization of the Judicial Yuan and of law courts of various grades shall be prescribed by law. |

TOP HOME [◆ Directory ROC Constitution (English)]

Chapter VIII. Examination

| Article 83 | The Examination Yuan shall be the highest examination organ of the State and shall have charge of matters relating to examination, employment, registration, service rating, scales of salary, promotion and transfer, security of tenure, commendation, pecuniary aid in case of death, retirement and old age pension. |

| Article 84 | The Examination Yuan shall have a President and a Vice President and a certain number of Members, all of whom shall be nominated and, with the consent the Control Yuan, appointed by the President of the Republic. |

| Article 85 | In the selection of public functionaries, a system of open competitive examination shall be put into operation, and examination shall be held in different areas, with prescribed numbers of persons to be selected according to various provinces and areas. No person shall be appointed to a public office unless he is qualified through examination. |

| Article 86 | The

following qualifications shall be determined and registered through

examination by the Examination Yuan in accordance with law:

Qualification for appointment as public functionaries; and Qualification for practice in specialized professions or as technicians. |

| Article 87 | The Examination Yuan may, with respect to matters under its charge , present statuory bills to the Legislative Yuan. |

| Article 88 | Members of the Examination Yuan shall be above partisanship and shall independently exercise their functions in accordance with law. |

| Article 89 | The organization of the Examination Yuan shall be prescribed by law. |

TOP HOME [◆ Directory ROC Constitution (English)]

Chapter IX. Control

| Article 90 | The Control Yuan shall be the highest control organ of the State and shall exercise the powers of consent, impeachment, censure, and auditing. |

| Article 91 | The

Control Yuan shall be composed of Members who shall be elected by Provincial

and Municipal Councils, the local Councils of Mongolia and Tibet, and Chinese

citizens residing abroad. Their numbers shall be determined in accordance with

the following provisions:

Five Members for each Province; Two Members for each municipality under the direct jurisdiction of the Executive Yuan; Eight Members for the Mongolian Leagues and Banners; Eight Members for Tibet; and Eight Members for Chinese citizens residing abroad. |

| Article 92 | The Control Yuan shall have a President and a Vice President, who shall be elected by and from among its Members. |

| Article 93 | Members of the Control Yuan shall serve a term of six years and shall be re-eligible. |

| Article 94 | When the Control Yual exercises the power of consent in accordance with this Constitution, it shall do so by resolution of a majority of the Members present at the meeting. |

| Article 95 | The Control Yuan may, in the exercise of its power of control, request the Executive Yuan and its Ministries and Commissions to submit to it for perusal the original orders issued by them and all other relevant documents. |

| Article 96 | The Control Yuan may, taking into account the work of the Executive Yuan and its various Ministries and Commissions, set up a certain number of committees to investigate their activities with a view to ascertaining whether or not they are guilty of violation of law or neglect of duty. |

| Article 97 | The

Control Yuan may, on the basis of the investigations and resolutions of its

committees, propose corrective measures and forward them to the Executive Yuan

and the Ministries and Commissions concerned, directing their attention to

effecting improvements.

When the Control Yuan deems a public functionary in the Central Government or in a local government guilty of neglect of duty or violation of law, it may propose corrective measures or institute an impeachment. If it involves a criminal offense, the case shall be turned over to a law court. |

| Article 98 | Impeachment by the Control Yuan of a public functionary in the Central Government or in a local government shall be instituted upon the proposal of one or more than one Member of the Control Yuan and the decision, after due consideration, by a committee composed of not less nine Members. |

| Article 99 | In case of impeachment by the Control Yuan of the personnel of the Judicial Yuan or of the Examination Yuan for neglect of duty or violation of law, the provisions of Articles 95, 97, and 98 of this Constitution shall be applicable. |

| Article 100 | Impeachment by the Control Yuan of the President or the Vice President shall be instituted upon the proposal of not less than one fourth of the whole body of Members of the Control Yuan and the resolution, after due consideration, by the majority of the whole body of members of the Control Yuan, and the same shall be presented to the National Assembly. |

| Article 101 | No Member of the Control Yuan shall be held responsible outside the Yuan for opinions expressed or votes cast in the Yuan. |

| Article 102 | No Member of the Control Yuan shall, except in case of flagrante delicto, be arrested or detained without the permission of the Control Yuan. |

| Article 103 | No member of the Control Yuan shall concurrently hold a public office or engage in any profession. |

| Article 104 | In the Control Yuan, there shall have an Auditor General who shall be nominated and, with the consent of the Legislative Yuan, appointed by the President of the Republic. |

| Article 105 | The Auditor General shall, within three months after presentation by the Executive Yuan of the final accounts of revenues and expenditures, complete the auditing thereof in accordance with law and submit an auditing report to the Legislative Yuan. |

| Article 106 | The organization of the Control Yuan shall be prescribed by law. |

TOP HOME [◆ Directory ROC Constitution (English)]

Chapter X. Powers of the Central and Local Governments

| Article 107 | In the following

matters, the Central Government shall have the power of legislation and

administration:

Foreign affairs; |

| Article 108 | In the following

matters, the Central Government shall have the power of legislation and

administration, but the Central Government may delegate the power of

Administration to the provincial and hsien governments:

General principles of provincial and hsien self-government; With respect to the various items enumerted in the preceding paragraph, the provinces may enact separate rules and regulations, provided they are not in conflict with national laws. |

| Article 109 | In the following

matters, the provinces shall have the power of legislation and administration,

but the provinces may delegate the power of administration to the hsien:

Provincial education, public health, industries, and communications; Except as otherwise provided by law, any of the matters enumerated in the various items of the preceding paragraph, in so far as it covers two or more provinces, may be undertaken jointly by the provinces concerned. When any province, in undertaking matters listed in any of the items of the first paragraph, finds its funds insufficient, it may, by resolution of the Legislative Yuan, obtain subsidies from the National Treasury. |

| Article 110 | In the following

matters, the hsien shall have the power of legislation and adminstration:

Hsien education, public health, industries and communications; Other matters delegated to the hsien in accordance with national laws and provincial Self-Government Regulations. Except as otherwise provided by law, any of the matters enumerated in the various items of the proceding paragraph, in so far as it covers two or more hsien, may be undertaken jointly by the hsien concerned. |

| Article 111 | Any matter not enumerated in Articles 107, 108, 109, and 110 shall fall within the jurisdiction of the Central Government, if it is national in nature; of the province, if it is provincial in nature; and of the hsien, if it concerns the hsien. In case of dispute, it shall be settled by the Legislative Yuan. |

TOP HOME [◆ Directory ROC Constitution (English)]

Chapter XI. System of Local Government

Section 1. The Province

| Article 112 | A Province may

convoke a Provincial Assembly to enact, in accordance with the General

Principles of Provincial and Hsien Self-Government, regulations, provided the said

regulations are not in conflict with the Constitution.

The organization of the provincial assembly and the election of the delegates shall be prescribed by law. |

| Article 113 | The Provincial

Self-Government Regulations shall include the following provisions:

In the province, there shall be a provincial council. Members of the Provincial council shall be elected by the people of the province. In the province, there shall be a provincial government with a Provincial Governor who be elected by the people of the Province. Relationship between the province and the hsien. The legislative power of the province shall be exercised by the Provincial Council. |

| Article 114 | The Provincial Self-Government Regulations shall, after enactment, be forthwith submitted to the Judicial Yuan.The Judicial Yuan, if it deems any part thereof unconstitutional, shall declare null and void the articles repugnant to the Constitution. |

| Article 115 | If, during the enforcement of Provincial Self-Goverment Regulations, there should arise any serious obstacle in the application of any of the articles contained therein, the Judical Yuan shall first summon the various parties concerned to present their views; and thereupon the Presidents of the Executive Yuan, Legislative Yuan, Judicial Yuan, Examination Yuan and Control Yuan shall form a Committee, with the President of Judicial Yuan as Chairman, to propose a formula for solution. |

| Article 116 | Provincial rules and regulations that are in conflict with national laws shall be null and void. |

| Article 117 | When doubt arises as to whether or not there is a conflict between provincial rules or regulations and national laws, interpretation thereon shall be made by the Judicial Yuan. |

| Article 118 | The self-government of municipalities under the direct jurisdiction of the Executive Yuan shall be prescribed by law. |

| Article 119 | The local self-government of Mongolian Leagues and Banners shall be prescribed by law. |

| Article 120 | The self-government system of Tibet shall be safeguarded. |

Section 2. The Hsien

| Article 121 | The hsien shall enforce hsien self-government. |

| Article 122 | A hsien may convoke a hsien assembly to enact,in accordance with the General Principles of Provincial and Hsien Self-Government, hsien self-government regulations, provide the said regulations are not in conflict with the Constitution or with provincial self-government regulations. |

| Article 123 | The people of the hsien shall, in accordance with law, exercise the rights of initiative and referendum in matters within the sphere of hsien self-government and shall, in accordance with law, exercise the rights of election and recall of the magistrate and other hsien self-government officials. |

| Article 124 | In the hsien, there

shall be a hsien council. Members of the hsien council shall be elected by the

people of the hsien.

The legislative power of the hsien shall be exercised by the hsien council. |

| Article 125 | Hsien rules and regulations that are in conflict with national laws, or with provincial rules and regulations, shall be null and void. |

| Article 126 | In the hsien, there shall be a hsien government with hsien magistrate who shall be elected by the people of the hsien. |

| Article 127 | The hsien magistrate shall have charge of hsien self-government and shall administer matters delegated to hsien by the central or provincial government. |

| Article 128 | The provisions governing the hsien shall apply mutatis mutandis to the municipality. |

TOP HOME [◆ Directory ROC Constitution (English)]

Chapter XII. Election, Recall, Initiative and Referendum

| Article 129 | The various kinds of elections prescribed in this Constitution, except as otherwise provided by this Constitution, shall be by universal, equal, and direct suffrage and by secret ballot. |

| Article 130 | Any citizen of the Republic of China who has attained the age of 20 years shall have the right of election in accordance with law. Except as otherwise provided by this Constitution or by law, any citizen who has attained the age of 23 years shall have the right of being elected in accordance with law. |

| Article 131 | All candidates in the various kinds of election prescribed in this Constitution shall openly campaign for their election. |

| Article 132 | Intimidation or inducements shall be strictly forbidden in elections. Suits arising in connection with elections shall be tried by courts. |

| Article 133 | A person elected may, in accordance with law, be recalled by his constituency. |

| Article 134 | In the various kinds of election, quotas of successful candidates shall be assigned to women; methods of implementation shall be prescribed by law. |

| Article 135 | The number of delegates to the National Assembly and the manner of their election from people in interior areas, who have their own conditions of living and habits, shall be prescribed by law. |

| Article 136 | The exercise of the rights of initiative and referendum shall be prescribed by law. |

TOP HOME [◆ Directory ROC Constitution (English)]

Chapter XIII. Fundamental National Policies

Section 1. National Defense

| Article 137 | The national defense

of the Republic of China shall have as its objective the safeguarding of

national security and the preservation of world peace.

The organization of national defense shall be prescribed by law. |

| Article 138 | The land, sea, and air forces of the whole country shall be above personal, regional, and party affiliations, shall be loyal to the state and shall protect the people. |

| Article 139 | No political party and no individual shall make use of armed forces as an instrument in the struggle for political powers. |

| Article 140 | No military man in active service may concurrently hold a civil office. |

Section 2. Foreign Policy

| Article 141 | The foreign policy of the Republic of China shall, in a spirit of independence and initiative and on the basis of the principles of equality and reciprocity, cultivate good-neighborliness with other nations, and respect treaties and the interests of Chinese citizens residing abroad, promote international cooperation, advance international justice and ensure world peace. |

Section 3. National Economy

| Article 142 | National economy shall be based on the Principle of People's Livelihood and shall seek to effect equalization of land ownership and restriction of private capital in order to attain a well-balanced sufficiency in national wealth and people's livelihood. |

| Article 143 | All land within the

territory of the Republic of China shall belong to the whole body of citizens.

Private ownership of land, acquired by the people in accordance with law, shall

be protected and restricted by law. Privately-owned land shall be liable to

taxation according to its value, and the Government may buy such land according

to its value.

Mineral deposits which are embedded in the land, and natural power which may, for economic purpose, be utilized for public benefit shall belong to the State, regardless of the fact that private individuals many have acquired ownership over such land. If the value of a picec of land has increased, not through the exertion of labor or the employment of capital, the State shall levy thereon an increment tax, the proceeds of which shall be enjoyed by the people in common. In the distribution and readjustment of land, the State shall in principle assist self-farming land-owners and persons who make use of the land by themselves, and shall also regulate their appropriate areas of operation. |

| Article 144 | Public utilities and other enterprises of a monopolistic nature shall, in principle, be under public operation. In cases permitted by law, they may be operated by private citizens. |

| Article 145 | With respect to

private wealth and privately operated enterprises, the State shall restrict

them by law if they are deemed detrimental to a balanced development of

national wealth and people's livelihood.

Cooperative enterprises shall receive encouragement and assistance from the State. Private citizens' productive enterprises and foreign trade shall receive encouragement, guidance and protection from the State. |

| Article 146 | The State shall, by the use of scientific techniques, develop water conservancy, increase the productivity of land, improve agricultural conditions, develop agricultural resources and hasten the industrialization of agriculture. |

| Article 147 | The Central

Government, in order to attain a balanced economic development among the

provinces, shall give appropriate aid to poor or unproductive provinces.

The provinces, in order to attain a balanced economic development among the hsien, shall give appropriate aid to poor or unproductive hsien. |

| Article 148 | Within the territory of the Republic of China, all goods shall be permitted to move freely from place to place. |

| Article 149 | Financial institutions shall, in accordance with law, be subject to State control. |

| Article 150 | The State shall extensively establish financial institutions for the common people, with a view to relieving unemployment. |

| Article 151 | With respect to Chinese citizens residing abroad, the State shall foster and protect development of their economic enterprises. |

Section 4. Social Security

| Article 152 | The State shall provide suitable opportunities for work to people who are able to work. |

| Article 153 | The State, in order

to improve the livelihood of laborers and farmers and to improve their

productive skills, shall enact laws and carry out policies for their

protection.

Women and children engaged in labor shall, according to their age and physical condition, be accorded special protection. |

| Article 154 | Captial and labor shall, in accordance with the principles of harmony and cooperation, promote productive enterprises. Conciliation and arbitration of disputes between capital and labor shall be prescribed by law. |

| Article 155 | The State, in order to promote social welfare, shall establish a social insurance system. To the aged and the infirm who are unable to earn a living, and to victims of unusual calamities, the State shall give appropriate assistance and relief. |

| Article 156 | The State, in order to consolidate the foundation of national existence and development, shall protect motherhood and carry out a policy for the promoting of the welfare of women and children. |

| Article 157 | The State, in order to improve national health, shall establish extensive services for sanitation and health protection, and a system of public medical service. |

Section 5. Education and Culture

| Article 158 | Education and culture shall aim at the development among the citizens of the national spirit, the spirit of self-government, national morality, good physique, scientific knowledge and ability to earn a living. |

| Article 159 | All citizens shall have an equal opportunity to receive an education. |

| Article 160 | All children of

school age from 6 to 12 years shall receive free primary education. Those from

poor families shall be supplied with book by the Government.

All citizens above school age who have not received primary education shall receive supplementary education free of charge and shall also be supplied with books by the Government. |

| Article 161 | The national, provincial, and local government shall extensively establish scholarships to assist students of good scholastic standing and exemplary conduct who lack the means to continue their school education. |

| Article 162 | All public and private educational and cultural institutions in the country shall, in accordance with law, be subject to State supervision. |

| Article 163 | The State shall pay due attention to the balanced development of education in different regions, and shall promote social education in order to raise the cultural standards of the citizens in general. Grants from the National Treasury shall be made to frontier regions and economically poor areas to help them meet their education and cultural expanse. The Central Government may either itself undertake the more important educational and cultural enterprises in such regions or give them financial assistance. |

| Article 164 | Expenditures of educational programs, scientific studies and cultural service shall not be, in respect of the Central Government, not less than 15 per cent of the total national budget; in respect of each province, not less than 25 percent of the total provincial budget; and in respect of each municipality or hsien, less than 35 percent of the total municipal or hsien budget. Educational and cultural foundations established in accordance with law shall, together with their property, be protected. |

| Article 165 | The State shall safeguard the livelihood of those who work in the field of education, sciences and arts, and shall, in accordance with the development of national economy, increase their remuneration from time to time. |

| Article 166 | The State shall encourage scientific discoveries and inventions, and shall protect ancient sites and articles of historical, cultural or artistic value. |

| Article 167 | The State shall give

encouragement or subsidies to the following enterprises or individuals:

Educational enterprises in the country which have been operated with good record by private individuals; Educational enterprises which have been operated with good record by Chinese citizens residing abroad; Persons who have made discoveries or inventions in the field of learning and technology; and Persons who have rendered long and meritorious services in the field of education. |

Section 6. Frontier Regions

| Article 168 | The State shall accord to various racial groups in the frontier regions legal protection of their status and shall give special assistance to their local self-government undertakings. |

| Article 169 | The State shall, in a positive manner, undertake and foster the develop of education, culture, communications, water conservancy, public health and other economic and social enterprises of the various racial group in the frontier regions. With respect to the utilization of land, the State shall, after taking into account the climatic conditions, the nature of the soil, and the life and habits of the people, adopt measures to protect the land and to assist in its development. |

TOP HOME [◆ Directory ROC Constitution (English)]

Chapter XIV. Enforcement and Amendment of the Constitution

| Article 170 | The term "law" as used in this Constitution, shall denote any legislative bill that have been passed by the Legislative Yuan and promulgated by the President of the Republic. |

| Article 171 | Laws that are in conflict with the Constitution shall be null and void. When doubt arises as to whether or not a law is in conflict with the Constitution, interpretation thereon shall be made by the Judicial Yuan. |

| Article 172 | Ordinance that are in conflict with the Constitution or with laws shall be null and void. |

| Article 173 | The Constitution shall be interpreted by the Judicial Yuan. |

| Article 174 | Amendments to the

Constitution shall be made in accordance with one of the following procedures:

Upon the propsal of one-fifth of the total number of delegates to the National Assembly and by a resolution of three-fourths of the delegates present at a meeting having a quorum of two-thirds of the entire Assembly, the Constitution may be amended. Upon the propsal of one-fourth of the members of the Legislative Yuan and by a resolution of three-fourths of the members present at a meeting having a quorum three-fourths of the members of the Yuan, an amendment may be drawn up and submitted to the National Assembly by way of referendum. Such a proposed amendment to the Constitution shall be publicly announced half a year before the National Assembly convenes. |

| Article 175 | Whenever necessary,

enforcement procedures in regard to any matter prescribed in this Constitution

shall be separately provided by law.

The preparatory procedures for the enforcement of this Constitution shall be decided upon by the same National Assembly which shall have adopted this Constitution. |

TOP HOME [◆ Directory ROC Constitution (English)]

===== ===== ===== ===== =====

◆ 中華民國憲法【全文】

- 第一章 總綱

- 第二章 人民之權利與義務

- 第三章 國民大會

- 第四章 總統

- 第五章 行政

- 第六章 立法

- 第七章 司法

- 第八章 考試

- 第九章 監察

- 第十章 中央與地方之權限

- 第十一章 地方制度

- 第十二章 選舉 罷免 創制決

- 第十三章 基本國策

- 第十四章 憲法之施行及修改

++++++++++ TOP HOME [next chapter] [previous chapter] ++++++++++

中華民國三十五年十二月二十五日制定

中華民國三十六年一月一日公布

中華民國三十六年十二月二十五日施行

第一章 總綱

| 第一條 | 中華民國基於三民主義,為民有民治民享之民主共和國。 |

| 第二條 | 中華民國之主權屬於國民全體。 |

| 第三條 | 具有中華民國國籍者為中華民國國民。 |

| 第四條 | 中華民國領土,依其固有之疆域,非經國民大會之決議,不得變更之。 |

| 第五條 | 中華民國各民族一律平等。 |

| 第六條 | 中華民國國旗定為紅地,左上角青天白日。 |

TOP HOME [◆ Directory ROC Constitution (Chinese)]

第二章 人民之權利與義務

| 第七條 | 中華民國人民,無分男女,宗教,種族,階級,黨派,在法律上一律平等。 |

| 第八條 | 人民身體之自由應予保障。除現行犯之逮捕由法律另定外,非經司法或警察機關依法定程序,不得逮捕拘禁。非由法院依法定程序,不得審問處罰。非依法定程序之逮捕,拘禁,審問,處罰,得拒絕之。

人民因犯罪嫌疑被逮捕拘禁時,其逮捕拘禁機關應將逮捕拘禁原因,以書面告知本人及其本人指定之親友,並至遲於二十四小時內移送該管法院審問。本人或他人亦得聲請該管法院,於二十四小時內向逮捕之機關提審。 法院對於前項聲請,不得拒絕,並不得先令逮捕拘禁之機關查覆。逮捕拘禁之機關,對於法院之提審,不得拒絕或遲延。 人民遭受任何機關非法逮捕拘禁時,其本人或他人得向法院聲請追究,法院不得拒絕,並應於二十四小時內向逮捕拘禁之機關追究,依法處理。 |

| 第九條 | 人民除現役軍人外,不受軍事審判。 |

| 第十條 | 人民有居住及遷徙之自由。 |

| 第十一條 | 人民有言論,講學,著作及出版之自由。 |

| 第十二條 | 人民有秘密通訊之自由。 |

| 第十三條 | 人民有信仰宗教之自由。 |

| 第十四條 | 人民有集會及結社之自由。 |

| 第十五條 | 人民之生存權,工作權及財產權,應予保障。 |

| 第十六條 | 人民有請願,訴願及訴訟之權。 |

| 第十七條 | 人民有選舉,罷免,創制及複決之權。 |

| 第十八條 | 人民有應考試服公職之權。 |

| 第十九條 | 人民有依法律納稅之義務。 |

| 第二十條 | 人民有依法律服兵役之義務。 |

| 第二十一條 | 人民有受國民教育之權利與義務。 |

| 第二十二條 | 凡人民之其他自由及權利,不妨害社會秩序公共利益者,均受憲法之保障。 |

| 第二十三條 | 以上各條列舉之自由權利,除為防止妨礙他人自由,避免緊急危難,維持社會秩序,或增進公共利益所必要者外,不得以法律限制之。 |

| 第二十四條 | 凡公務員違法侵害人民之自由或權利者,除依法律受懲戒外,應負刑事及民事責任。被害人民就其所受損害,並得依法律向國家請求賠償。 |

TOP HOME [◆ Directory ROC Constitution (Chinese)]

第三章 國民大會

| 第二十五條 | 國民大會依本憲法之規定,代表全國國民行使政權。 |

| 第二十六條 | 國民大會以左列代表組織之:

一、每縣市及其同等區域各選出代表一人,但其人口逾五十萬人者,每增加五十萬人,增選代表一人。縣市同等區域以法律定之。 二、蒙古選出代表,每盟四人,每特別旗一人。 三、西藏選出代表,其名額以法律定之。 四、各民族在邊疆地區選出代表,其名額以法律定之。 五、僑居國外之國民選出代表,其名額以法律定之。 六、職業團體選出代表,其名額以法律定之。 七、婦女團體選出代表,其名額以法律定之。 |

| 第二十七條 | 國民大會之職權如左:

一、選舉總統副總統。 二、罷免總統副總統。 三、修改憲法。 四、複決立法院所提之憲法修正案。 關於創制複決兩權,除前項第三第四兩款規定外,俟全國有半數之縣市曾經行使創制複決兩項政權時,由國民大會制定辦法並行使之。 |

| 第二十八條 | 國民大會代表每六年改選一次。 每屆國民大會代表之任期至次屆國民大會開會之日為止。 現任官吏不得於其任所所在地之選舉區當選為國民大會代表。 |

| 第二十九條 | 國民大會於每屆總統任滿前九十日集會,由總統召集之。 |

| 第三十條 | 國民大會遇有左列情形之一時,召集臨時會:

一、依本憲法第四十九條之規定,應補選總統副總統時。 二、依監察院之決議,對於總統副總統提出彈劾案時。 三、依立法院之決議,提出憲法修正案時。 四、國民大會代表五分之二以上請求召集時。 國民大會臨時會,如依前項第一款或第二款應召集時,由立法院院長通告集會。依第三款或第四款應召集時,由總統召集之。 |

| 第三十一條 | 國民大會之開會地點在中央政府所在地。 |

| 第三十二條 | 國民大會代表在會議時所為之言論及表決,對會外不負責任。 |

| 第三十三條 | 國民大會代表,除現行犯外,在會期中,非經國民大會許可,不得逮捕或拘禁。 |

| 第三十四條 | 國民大會之組織,國民大會代表之選舉罷免,及國民大會行使職權之程序,以法律定之。 |

TOP HOME [◆ Directory ROC Constitution (Chinese)]

第四章 總統

| 第三十五條 | 總統為國家元首,對外代表中華民國。 |

| 第三十六條 | 總統統率全國陸海空軍。 |

| 第三十七條 | 總統依法公布法律,發布命令,須經行政院院長之副署,或行政院院長及有關部會首長之副署。 |

| 第三十八條 | 總統依本憲法之規定,行使締結條約及宣戰媾和之權。 |

| 第三十九條 | 總統依法宣布戒嚴,但須經立法院之通過或追認。立法院認為必要時,得決議移請總統解嚴。 |

| 第四十條 | 總統依法行使大赦,特赦,減刑及復權之權。 |

| 第四十一條 | 總統依法任免文武官員。 |

| 第四十二條 | 總統依法授與榮典。 |

| 第四十三條 | 國家遇有天然災害,癘疫,或國家財政經濟上有重大變故,須為急速處分時,總統於立法院休會期間,得經行政院會議之決議,依緊急命令法,發布緊急命令,為必要之處置,但須於發布命令後一個月內提交立法院追認。如立法院不同意時,該緊急命令立即失效。 |

| 第四十四條 | 總統對於院與院間之爭執,除本憲法有規定者外,得召集有關各院院長會商解決之。 |

| 第四十五條 | 中華民國國民年滿四十歲者得被選為總統副總統。 |

| 第四十六條 | 總統副總統之選舉,以法律定之。 |

| 第四十七條 | 總統副總統之任期為六年,連選得連任一次。 |

| 第四十八條 | 總統應於就職時宣誓,誓詞如左:

「余謹以至誠,向全國人民宣誓,余必遵守憲法,盡忠職務,增進人民福利,保衛國家,無負國民付託。如違誓言,願受國家嚴厲之制裁。謹誓。」 |

| 第四十九條 | 總統缺位時,由副總統繼任,至總統任期屆滿為止。總統副總統均缺位時,由行政院院長代行其職權,並依本憲法第三十條之規定,召集國民大會臨時會,補選總統、副總統,其任期以補足原任總統未滿之任期為止。

總統因故不能視事時,由副總統代行其職權。總統副總統均不能視事時,由行政院院長代行其職權。 |

| 第五十條 | 總統於任滿之日解職。如屆期次任總統尚未選出,或選出後總統副總統均未就職時,由行政院院長代行總統職權。 |

| 第五十一條 | 行政院院長代行總統職權時,其期限不得逾三個月。 |

| 第五十二條 | 總統除犯內亂或外患罪外,非經罷免或解職,不受刑事上之訴究。 |

TOP HOME [◆ Directory ROC Constitution (Chinese)]

第五章 行政

| 第五十三條 | 行政院為國家最高行政機關。 |

| 第五十四條 | 行政院設院長副院長各一人,各部會首長若干人,及不管部會之政務委員若干人。 |

| 第五十五條 | 行政院院長由總統提名,經立法院同意任命之。立法院休會期間,行政院院長辭職或出缺時,由行政院副院長代理其職務,但總統須於四十日內咨請立法院召集會議,提出行政院院長人選徵求同意。行政院院長職務,在總統所提行政院院長人選未經立法院同意前,由行政院副院長暫行代理。 |

| 第五十六條 | 行政院副院長,各部會首長及不管部會之政務委員,由行政院院長提請總統任命之。 |

| 第五十七條 | 行政院依左列規定,對立法院負責:

一、行政院有向立法院提出施政方針及施政報告之責。立法委員在開會時,有向行政院院長及行政院各部會首長質詢之權。 二、立法院對於行政院之重要政策不贊同時,得以決議移請行政院變更之。行政院對於立法院之決議,得經總統之核可,移請立法院覆議。覆議時,如經出席立法委員三分之二維持原決議,行政院院長應即接受該決議或辭職。 三、行政院對於立法院決議之法律案,預算案,條約案,如認為有窒礙難行時,得經總統之核可,於該決議案送達行政院十日內,移請立法院覆議。覆議時,如經出席立法委員三分之二維持原案,行政院院長應即接受該決議或辭職。 |

| 第五十八條 | 行政院設行政院會議,由行政院院長,副院長,各部會首長及不管部會之政務委員組織之,以院長為主席。

行政院院長,各部會首長,須將應行提出於立法院之法律案,預算案,戒嚴案,大赦案,宣戰案,媾和案,條約案及其他重要事項,或涉及各部會共同關係之事項,提出於行政院會議議決之。 |

| 第五十九條 | 行政院於會計年度開始三個月前,應將下年度預算案提出於立法院。 |

| 第六十條 | 行政院於會計年度結束後四個月內,應提出決算於監察院。 |

| 第六十一條 | 行政院之組織,以法律定之。 |

TOP HOME [◆ Directory ROC Constitution (Chinese)]

第六章 立法

| 第六十二條 | 立法院為國家最高立法機關,由人民選舉之立法委員組織之,代表人民行使立法權。 |

| 第六十三條 | 立法院有議決法律案,預算案,戒嚴案,大赦案,宣戰案,媾和案,條約案及國家其他重要事項之權。 |

| 第六十四條 | 立法院立法委員依左列規定選出之:

一、各省,各直轄市選出者,其人口在三百萬以下者五人,其人口超過三百萬者,每滿一百萬人增選一人。 二、蒙古各盟旗選出者。 三、西藏選出者。 四、各民族在邊疆地區選出者。 五、僑居國外之國民選出者。 六、職業團體選出者。 立法委員之選舉及前項第二款至第六款立法委員名額之分配,以法律定之。婦女在第一項各款之名額,以法律定之。 |

| 第六十五條 | 立法委員之任期為三年,連選得連任,其選舉於每屆任滿前三個月內完成之。 |

| 第六十六條 | 立法院設院長副院長各一人,由立法委員互選之。 |

| 第六十七條 | 立法院得設各種委員會。

各種委員會得邀請政府人員及社會上有關係人員到會備詢。 |

| 第六十八條 | 立法院會期,每年兩次,自行集會,第一次自二月至五月底,第二次自九月至十二月底,必要時得延長之。 |

| 第六十九條 | 立法院遇有左列情事之一時,得開臨時會:

一、總統之咨請。 二、立法委員四分之一以上之請求。 |

| 第七十條 | 立法院對於行政院所提預算案,不得為增加支出之提議。 |

| 第七十一條 | 立法院開會時,關係院院長及各部會首長得列席陳述意見。 |

| 第七十二條 | 立法院法律案通過後,移送總統及行政院,總統應於收到後十日內公布之,但總統得依照本憲法第五十七條之規定辦理。 |

| 第七十三條 | 立法委員在院內所為之言論及表決,對院外不負責任。 |

| 第七十四條 | 立法委員,除現行犯外,非經立法院許可,不得逮捕或拘禁。 |

| 第七十五條 | 立法委員不得兼任官吏。 |

| 第七十六條 | 立法院之組織,以法律定之。 |

TOP HOME [◆ Directory ROC Constitution (Chinese)]

第七章 司法

| 第七十七條 | 司法院為國家最高司法機關,掌理民事,刑事,行政訴訟之審判,及公務員之懲戒。 |

| 第七十八條 | 司法院解釋憲法,並有統一解釋法律及命令之權。 |

| 第七十九條 | 司法院設院長副院長各一人,由總統提名,經監察院同意任命之。

司法院設大法官若干人,掌理本憲法第七十八條規定事項,由總統提名,經監察院同意任命之。 |

| 第八十條 | 法官須超出黨派以外,依據法律獨立審判,不受任何干涉。 |

| 第八十一條 | 法官為終身職,非受刑事或懲戒處分,或禁治產之宣告,不得免職。非依法律,不得停職,轉任或減俸。 |

| 第八十二條 | 司法院及各級法院之組織,以法律定之。 |

TOP HOME [◆ Directory ROC Constitution (Chinese)]

第八章 考試

| 第八十三條 | 考試院為國家最高考試機關,掌理考試,任用,銓敘,考績,級俸,陞遷,保障,褒獎,撫卹,退休,養老等事項。 |

| 第八十四條 | 考試院設院長副院長各一人,考試委員若干人,由總統提名,經監察院同意任命之。 |

| 第八十五條 | 公務人員之選拔,應實行公開競爭之考試制度,並應按省區分別規定名額,分區舉行考試,非經考試及格者,不得任用。 |

| 第八十六條 | 左列資格,應經考試院依法考選銓定之:

一、公務人員任用資格。 二、專門職業及技術人員執業資格。 |

| 第八十七條 | 考試院關於所掌事項,得向立法院提出法律案。 |

| 第八十八條 | 考試委員須超出黨派以外,依據法律獨立行使職權。 |

| 第八十九條 | 考試院之組織,以法律定之。 |

TOP HOME [◆ Directory ROC Constitution (Chinese)]

第九章 監察

| 第九十條 | 監察院為國家最高監察機關,行使同意,彈劾,糾舉及審計權。 |

| 第九十一條 | 監察院設監察委員,由各省市議會,蒙古西藏地方議會,及華僑團體選舉之。其名額分配依左列之規定:

一、每省五人。 二、每直轄市二人。 三、蒙古各盟旗共八人。 四、西藏八人。 五、僑居國外之國民八人。 |

| 第九十二條 | 監察院設院長副院長各一人,由監察委員互選之。 |

| 第九十三條 | 監察委員之任期為六年,連選得連任。 |

| 第九十四條 | 監察院依本憲法行使同意權時,由出席委員過半數之議決行之。 |

| 第九十五條 | 監察院為行使監察權,得向行政院及其各部會調閱其所發布之命令及各種有關文件。 |

| 第九十六條 | 監察院得按行政院及其各部會之工作,分設若干委員會,調查一切設施,注意其是否違法或失職。 |

| 第九十七條 | 監察院經各該委員會之審查及決議,得提出糾正案,移送行政人員,認為有失職或違法情事,得提出糾舉案或彈劾案,如涉及刑事,應移送法院辦理。 |

| 第九十八條 | 監察院對於中央及地方公務人員之彈劾案,須經監察委員一人以上之提議,九人以上之審查及決定,始得提出。 |

| 第九十九條 | 監察院對於司法院或考試院人員失職或違法之彈劾,適用本憲法第九十五條,第九十七條,及第九十八條之規定。 |

| 第一百條 | 監察院對於總統副總統之彈劾案,須有全體監察委員四分之一以上之提議,全體監察委員過半數之審查及決議,向國民大會提出之。 |

| 第一百零一條 | 監察委員在院內所為之言論及表決,對院外不負責任。 |

| 第一百零二條 | 監察委員,除現行犯外,非經監察院許可,不得逮捕或拘禁。 |

| 第一百零三條 | 監察委員不得兼任其他公職或執行業務。 |

| 第一百零四條 | 監察院設審計長,由總統提名,經立法院同意任命之。 |

| 第一百零五條 | 審計長應於行政院提出決算後三個月內,依法完成其審核,並提出審核報告於立法院。 |

| 第一百零六條 | 監察院之組織,以法律定之。 |

TOP HOME [◆ Directory ROC Constitution (Chinese)]

第十章 中央與地方之權限

| 第一百零七條 | 左列事項,由中央立法並執行之:

一、外交。 二、國防與國防軍事。 三、國籍法,及刑事民事商事之法律。 四、司法制度。 五、航空,國道,國有鐵路,航政,郵政及電政。 六、中央財政與國稅。 七、國稅與省稅縣稅之劃分。 八、國營經濟事業。 九、幣制及國家銀行。 十、度量衡。 十一、國際貿易政策。 十二、涉外之財政經濟事項。 十三、其他依本憲法所定關於中央之事項。 |

| 第一百零八條 | 左列事項,由中央立法並執行之或交由省縣執行之:

一、省縣自治通則。 二、行政區劃。 三、森林,工礦及商業。 四、教育制度。 五、銀行及交易所制度。 六、航業及海洋漁業。 七、公用事業。 八、合作事業。 九、二省以上之水陸交通運輸。 十、二省以上之水利,河道及農牧事業。 十一、中央及地方官吏之銓敘,任用,糾察及保障。 十二、土地法。 十三、勞動法及其他社會立法。 十四、公用徵收。 十五、全國戶口調查及統計。 十六、移民及墾殖。 十七、警察制度。 十八、公共衛生。 十九、賑濟,撫卹及失業救濟。 二十、有關文化之古籍,古物及古蹟之保存。 前項各款,省於不牴觸國家法律內,得制定單行法規。 |

| 第一百零九條 | 左列事項,由省立法並執行之,或交由縣執行之:

一、省教育,衛生,實業及交通。 二、省財產之經營及處分。 三、省市政。 四、省公營事業。 五、省合作事業。 六、省農林,水利,漁牧及工程。 七、省財政及省稅。 八、省債。 九、省銀行。 十、省警政之實施。 十一、省慈善及公益事項。 十二、其他依國家法律賦予之事項。 前項各款,有涉及二省以上者,除法律別有規定外,得由有關各省共同辦理。各省辦理第一項各款事務,其經費不足時,經立法院議決,由國庫補助之。 |

| 第一百十條 | 左列事項,由縣立法並執行之:

一、縣教育,衛生,實業及交通。 二、縣財產之經營及處分。 三、縣公營事業。 四、縣合作事業。 五、縣農林,水利,漁牧及工程。 六、縣財政及縣稅。 七、縣債。 八、縣銀行。 九、縣警衛之實施。 十、縣慈善及公益事項。 十一、其他依國家法律及省自治法賦予之事項。 前項各款,有涉及二縣以上者,除法律別有規定外,得由有關各縣共同辦理。 |

| 第一百十一條 | 除第一百零七條,第一百零八條,第一百零九條及第一百十條列舉事項外,如有未列舉事項發生時,其事務有全國一致之性質者屬於中央,有全省一致之性質者屬於省,有一縣之性質者屬於縣。遇有爭議時,由立法院解決之。 |

TOP HOME [◆ Directory ROC Constitution (Chinese)]

第十一章 地方制度

———第一節 省

| 第一百十二條 | 省得召集省民代表大會,依據省縣自治通則,制定省自治法,但不得與憲法牴觸。

省民代表大會之組織及選舉,以法律定之。 |

| 第一百十三條 | 省自治法應包含左列各款:

一、省設省議會,省議會議員由省民選舉之。 二、省設省政府,置省長一人。省長由省民選舉之。 三、省與縣之關係。 屬於省之立法權,由省議會行之。 |

| 第一百十四條 | 省自治法制定後,須即送司法院。司法院如認為有違憲之處,應將違憲條文宣布無效。 |

| 第一百十五條 | 省自治法施行中,如因其中某條發生重大障礙,經司法院召集有關方面陳述意見後,由行政院院長,立法院院長,司法院院長,考試院院長與監察院院長組織委員會,以司法院院長為主席,提出方案解決之。 |

| 第一百十六條 | 省法規與國家法律牴觸者無效。 |

| 第一百十七條 | 省法規與國家法律有無牴觸發生疑義時,由司法院解釋之。 |

| 第一百十八條 | 直轄市之自治,以法律定之。 |

| 第一百十九條 | 蒙古各盟旗地方自治制度,以法律定之。 |

| 第一百二十條 | 西藏自治制度,應予以保障。 |

———第二節 縣

| 第一百二十一條 | 縣實行縣自治。 |

| 第一百二十二條 | 縣得召集縣民代表大會,依據省縣自治通則,制定縣自治法,但不得與憲法及省自治法牴觸。 |

| 第一百二十三條 | 縣民關於縣自治事項,依法律行使創制複決之權,對於縣長及其他縣自治人員,依法律行使選舉罷免之權。 |

| 第一百二十四條 | 縣設縣議會。縣議會議員由縣民選舉之。屬於縣之立法權,由縣議會行之。 |

| 第一百二十五條 | 縣單行規章,與國家法律或省法規牴觸者無效。 |

| 第一百二十六條 | 縣設縣政府,置縣長一人。縣長由縣民選舉之。 |

| 第一百二十七條 | 縣長辦理縣自治,並執行中央及省委辦事項。 |

| 第一百二十八條 | 市準用縣之規定。 |

TOP HOME [◆ Directory ROC Constitution (Chinese)]

第十二章 選舉 罷免 創制 複決

| 第一百二十九條 | 本憲法所規定之各種選舉,除本憲法別有規定外,以普通,平等,直接及無記名投票之方法行之。 |

| 第一百三十條 | 中華民國國民年滿二十歲者,有依法選舉之權。除本憲法及法律別有規定者外,年滿二十三歲者,有依法被選舉之權。 |

| 第一百三十一條 | 本憲法所規定各種選舉之候選人,一律公開競選。 |

| 第一百三十二條 | 選舉應嚴禁威脅利誘。選舉訴訟,由法院審判之。 |

| 第一百三十三條 | 被選舉人得由原選舉區依法罷免之。 |

| 第一百三十四條 | 各種選舉,應規定婦女當選名額,其辦法以法律定之。 |

| 第一百三十五條 | 內地生活習慣特殊之國民代表名額及選舉,其辦法以法律定之。 |

| 第一百三十六條 | 創制複決兩權之行使,以法律定之。 |

TOP HOME [◆ Directory ROC Constitution (Chinese)]

第十三章 基本國策

———第一節 國防

| 第一百三十七條 | 中華民國之國防,以保衛國家安全,維護世界和平為目的。國防之組織,以法律定之。 |

| 第一百三十八條 | 全國陸海空軍,須超出個人,地域及黨派關係以外,效忠國家,愛護人民。 |

| 第一百三十九條 | 任何黨派及個人不得以武裝力量為政爭之工具。 |

| 第一百四十條 | 現役軍人不得兼任文官。 |

———第二節 外交

| 第一百四十一條 | 中華民國之外交,應本獨立自主之精神,平等互惠之原則,敦睦邦交,尊重條約及聯合國憲章,以保護僑民權益,促進國際合作,提倡國際正義,確保世界和平。 |

———第三節 國民經濟

| 第一百四十二條 | 國民經濟應以民生主義為基本原則,實施平均地權,節制資本,以謀國計民生之均足。 |

| 第一百四十三條 | 中華民國領土內之土地屬於國民全體。人民依法取得之土地所有權,應受法律之保障與限制。私有土地應照價納稅,政府並得照價收買。

附著於土地之礦,及經濟上可供公眾利用之天然力,屬於國家所有,不因人民取得土地所有權而受影響。 土地價值非因施以勞力資本而增加者,應由國家徵收土地增值稅,歸人民共享之。 國家對於土地之分配與整理,應以扶植自耕農及自行使用土地人為原則,並規定其適當經營之面積。 |

| 第一百四十四條 | 公用事業及其他有獨佔性之企業,以公營為原則,其經法律許可者,得由國民經營之。 |

| 第一百四十五條 | 國家對於私人財富及私營事業,認為有妨害國計民生之平衡發展者,應以法律限制之。

合作事業應受國家之獎勵與扶助。 國民生產事業及對外貿易,應受國家之獎勵,指導及保護。 |

| 第一百四十六條 | 國家應運用科學技術,以興修水利,增進地力,改善農業環境,規劃土地利用,開發農業資源,促成農業之工業化。 |

| 第一百四十七條 | 中央為謀省與省間之經濟平衡發展,對於貧瘠之省,應酌予補助。

省為謀縣與縣間之經濟平衡發展,對於貧瘠之縣,應酌予補助。 |

| 第一百四十八條 | 中華民國領域內,一切貨物應許自由流通。 |

| 第一百四十九條 | 金融機構,應依法受國家之管理。 |

| 第一百五十條 | 國家應普設平民金融機構,以救濟失業。 |

| 第一百五十一條 | 國家對於僑居國外之國民,應扶助並保護其經濟事業之發展。 |

———第四節 社會安全

| 第一百五十二條 | 人民具有工作能力者,國家應予以適當之工作機會。 |

| 第一百五十三條 | 國家為改良勞工及農民之生活,增進其生產技能,應制定保護勞工及農民之法律,實施保護勞工及農民之政策。 婦女兒童從事勞動者,應按其年齡及身體狀態,予以特別之保護。 |

| 第一百五十四條 | 勞資雙方應本協調合作原則,發展生產事業。勞資糾紛之調解與仲裁,以法律定之。 |

| 第一百五十五條 | 國家為謀社會福利,應實施社會保險制度。人民之老弱殘廢,無力生活,及受非常災害者,國家應予以適當之扶助與救濟。 |

| 第一百五十六條 | 國家為奠定民族生存發展之基礎,應保護母性,並實施婦女兒童福利政策。 |

| 第一百五十七條 | 國家為增進民族健康,應普遍推行衛生保健事業及公醫制度。 |

———第五節 教育文化

| 第一百五十八條 | 教育文化,應發展國民之民族精神,自治精神,國民道德,健全體格,科學及生活智能。 |

| 第一百五十九條 | 國民受教育之機會一律平等。 |

| 第一百六十條 | 六歲至十二歲之學齡兒童,一律受基本教育,免納學費。其貧苦者,由政府供給書籍。

已逾學齡未受基本教育之國民,一律受補習教育,免納學費,其書籍亦由政府供給。 |

| 第一百六十一條 | 各級政府應廣設獎學金名額,以扶助學行俱優無力升學之學生。 |

| 第一百六十二條 | 全國公私立之教育文化機關,依法律受國家之監督。 |

| 第一百六十三條 | 國家應注重各地區教育之均衡發展,並推行社會教育,以提高一般國民之文化水準,邊遠及貧瘠地區之教育文化經費,由國庫補助之。其重要之教育文化事業,得由中央辦理或補助之。 |

| 第一百六十四條 | 教育,科學,文化之經費,在中央不得少於其預算總額百分之十五,在省不得少於其預算總額百分之二十五,在市縣不得少於其預算總額百分之三十五。其依法設置之教育文化基金及產業,應予以保障。 |

| 第一百六十五條 | 國家應保障教育,科學,藝術工作者之生活,並依國民經濟之進展,隨時提高其待遇。 |

| 第一百六十六條 | 國家應獎勵科學之發明與創造,並保護有關歷史文化藝術之古蹟古物。 |

| 第一百六十七條 | 國家對於左列事業或個人,予以獎勵或補助:

一、國內私人經營之教育事業成績優良者。 二、僑居國外國民之教育事業成績優良者。 三、於學術或技術有發明者。 四、從事教育久於其職而成績優良者。 |

———第六節 邊疆地區

| 第一百六十八條 | 國家對於邊疆地區各民族之地位,應予以合法之保障,並於其地方自治事業,特別予以扶植。 |

| 第一百六十九條 | 國家對於邊疆地區各民族之教育,文化,交通,水利,衛生,及其他經濟,社會事業,應積極舉辦,並扶助其發展,對於土地使用,應依其氣候,土壤性質,及人民生活習慣之所宜,予以保障及發展。 |

TOP HOME [◆ Directory ROC Constitution (Chinese)]

第十四章 憲法之施行及修改

| 第一百七十條 | 本憲法所稱之法律,謂經立法院通過,總統公布之法律。 |

| 第一百七十一條 | 法律與憲法牴觸者無效。

法律與憲法有無牴觸發生疑義時,由司法院解釋之。 |

| 第一百七十二條 | 命令與憲法或法律牴觸者無效。 |

| 第一百七十三條 | 憲法之解釋,由司法院為之。 |

| 第一百七十四條 | 憲法之修改,應依左列程序之一為之:

一、由國民大會代表總額五分之一提議,三分之二之出席,及出席代表四分之三之決議,得修改之。 二、由立法院立法委員四分之一之提議,四分之三之出席,及出席委員四分之三之決議,擬定憲法修正案,提請國民大會複決。此項憲法修正案應於國民大會開會前半年公告之。 |

| 第一百七十五條 | 本憲法規定事項,有另定實施程序之必要者,以法律定之。 |

本憲法施行之準備程序由制定憲法之國民大會議定之。

TOP HOME [◆ Directory ROC Constitution (Chinese)]

===== ===== ===== ===== =====

◆ Temporary Provisions Effective During the Period of Communist Rebellion

- Original version (1948)

- Amended version (1960)

- Amended version (1966)

- Amended, final version (1972)

++++++++++ TOP HOME [next chapter] [previous chapter] ++++++++++

Original version (1948)

Temporary Provisions Effective During the Period of National Crisis

(Adopted by the National Assembly on April 18, 1948, and promulgated by the National Government on May 10, 1948)

In accordance with the procedure prescribed in Item (1) of Article 174 of the Constitution, the following temporary provisions to be effective during the period of national crisis are hereby adopted:

The President during the period of national crisis may, by resolution of the Executive Yuan Council, take emergency measures to avert an imminent danger to the security of the State or of the people or to cope with any serious financial or economic crisis, without being subject to the procedural restrictions prescribed in Article 39 or Article 43 of the Constitution.

The emergency measures mentioned in the preceding paragraph may be modified or abrogated by the Legislative Yuan in accordance with Item (2) of Article 57 of the Constitution.

The period of national crisis may be declared terminated by the President on his own initiative or at the request of the Legislative Yuan.

The President shall convoke an extraordinary session of the first National Assembly on a date not later than December 25, 1950, to discuss all proposed amendments to the Constitution. If at that time the period of national crisis has not yet been declared teminated in accordance with foregoing provisions, that National Assembly in an extraordinary session shall decide whether the temporary provisions are to remain in force or to be abrogated.

(Source: China Handbook 1956-57, p. 815)

TOP HOME [◆ Directory Temporary Provisions (English)]

Amended version (1960)

Temporary Provisions Effective During the Period of Communist Rebellion

(Adopted by the National Assembly on April 18, 1948, promulgated by the National Government on May 10, 1948, and amended by the National Assembly on March 11, 1960)

In accordance with the procedure prescribed in Paragraph 1 of Article 174 of the Constitution, the following Temporary Provisions to be effective during the Period of Communist Rebellion are hereby enacted:

| 1. | The President during the Period of Communist Rebellion may, by resolution of the Executive Yuan Council, take emergency measures to avert an imminent danger to the security of the State or of the people or to cope with any serious financial or economic crisis, without being subject to the procedural restrictions prescribed in Article 39 or Article 43 of the Constitution. |

| 2. | The emergency measures mentioned in the preceding paragraph may be modified or abrogated by the Legislative Yuan in accordance with Paragraph 2 of Article 57 of the Constitution. |

| 3. | During the Period of Communist Rebellion, the President and the Vice President may be reelected without being subject to the two-term restriction prescribed in Article 47 of the Constitution. |

| 4. | An organ shall be established after the conclusion of the third plenary session of the National Assembly to study and draft proposals relating to the exercise of the powers of initiative and referendum by the National Assembly. These, together with other proposals pertaining to constitutional amendment, shall be discussed by the National Assembly at an extraordinary session to be convoked by the President. |

| 5. | The extraordinary session of the National Assembly shall be convoked by the third President elected under this Constitution, at an appropriate time during his term of office. |

| 6. | The termination of the Period of Communist Rebellion shall be declared by the President. |

| 7. | Amendment or abrogation of the Temporary Provisions shall be resolved by the National Assembly. |

(Source: China Yearbook 1961-62, p. 915)

TOP HOME [◆ Directory Temporary Provisions (English)]

Amended version (1966)

Temporary Provisions Effective During the Period of Communist Rebellion

(Adopted by the National Assembly on April 18, 1948, promulgated by the National Government on May 10, 1948, amended by the National Assembly on March 11, 1960, amended by the extraordinary session of the National Assembly on February 7, 1966 and amended by the National Assembly on March 19, 1966)

In accordance with the procedure prescribed in Paragraph 1 of Article 174 of the Constitution, the following Temporary Provisions to be effective during the Period of Communist Rebellion are hereby enacted:

| 1. | The President during the Period of Communist Rebellion may, by resolution of the Executive Yuan Council, take emergency measures to avert an imminent danger to the security of the State or of the people, or to cope with any serious financial or economic crisis, without being subject to the procedural restrictions prescribed in Article 39 or Article 43 of the Constitution. |

| 2. | The emergency measures mentioned in the preceding paragraph may be modified or abrogated by the Legislative Yuan in accordance with Paragraph 2 of Article 57 of the Constitution. |

| 3. | During the Period of Communist Rebellion, the President and the Vice President may be reelected without being subject to the two-term restriction prescribed in Article 47 of the Constitution. |

| 4. | During the Period of Communist Rebellion, the President is authorized to establish, in accordance with the constitutional system, an organ for making major policy decisions concerned with national mobilization and suppression of the Communist rebellion and for assuming administrative control in war zones. |

| 5. | To meet the requirements of national mobilization and suppression of the Communist rebellion, the President may make adjustments in the administrative and personnel organs of the Central Government, and also may initiate and promulgate for enforcement regulations providing for elections to fill, according to law, those elective offices at the Central Government level which have become vacant for legitimate reasons, or for which additional representation is called for because of population increases, in areas that are free and/or newly recovered. |

| 6. | During the Period of Communist Rebellion, the National Assembly may enact measures to initiate principles concerning central government laws and submit central government laws to referendum without being subject to the restriction prescribed in Paragraph 2 of Article 27 of the Constitution. |

| 7. | During the Period of Communist Rebellion, the President may, when he deems necessary, convoke an extraordinary session of the National Assembly to discuss initiative or referendum measures. |

| 8. | The National Assembly shall establish an organ to study, during its recess, problems relating to constitutional rule. |

| 9. | The termination of the Period of Communist Rebellion shall be declared by the President. |

| 10. | Amendment or abrogation of the Temporary Provisions shall be resolved by the National Assembly. |

(Source: China Yearbook 1970-71, p. 720)

TOP HOME [◆ Directory Temporary Provisions (English)]

Amended, final version (1972)

Temporary Provisions Effective During the Period of Communist Rebellion

(Adopted by the National Assembly on April 18, 1948, promulgated by the National Government on May 10, 1948, amended by the National Assembly on March 11, 1960, Amended by the extraordinary session of the National Assembly on February 7, 1966, amended by the National Assembly at its ninth plenary meeting March 17, 1972)

In accordance with the procedure prescribed in Paragraph 1 of Article 174 of the Constitution, the following Temporary Provisions to be effective during the Period of Communist Rebellion are hereby enacted:

| 1. | The President during the Period of Communist Rebellion may, by resolution of the Executive Yuan Council, take emergency measures to avert any imminent danger to the security of the State or of the people or to cope with any serious financial or economic crisis, without being subject to the procedural restrictions prescribed in Article 39 or Article 43 of the Constitution. |

| 2. | The emergency measures mentioned in the preceding paragraph may be modified or abrogated by the Legislative Yuan in accordance with Paragraph 2 of Article 57 of the Constitution. |

| 3. | During the Period of the Communist Rebellion, the President and the Vice President may be reelected without being subject to the two-term restriction prescribed in Article 47 of the Constitution. |

| 4. | During the period of Communist Rebellion, the President is authorized to establish, in accordance with the constitutional system, an organ for making major policy decisions concerned with national mobilization and suppression of the Communist rebellion and for assuming administrative control in war zones. |

| 5. | To meet the requirements of national mobilization and suppression of the Communist rebellion, the President may make adjustments in the administrative and personnel organs of the Central Government, as well as their organizations. |

| 6. | During the period of national mobilization and the suppression of the Communist rebellion, the President may,

in accordance with the following stipulations, initiate and promulgate for enforcement regulations providing for elections to strengthen

elective offices at the Central Government level without being subject to the restrictions prescribed in Article 26, Article 64, or Article 91